The Truth Shall Set You Free (Eventually)

Part 1 of a Multi-Part Journey Through Jonathan Cook’s Creative Storytelling

In this article, I’m responding to

's piece titled “Israeli torture chambers aren't new. They are what provoked the violence of Oct 7.”Jonathan Cook claims to be an “independent journalist.” I understand the “independent” part—nothing screams independence like boldly sharing unverified opinions online. The “journalist” part, however, is a little more questionable. At this point, Jonathan seems more like an “opinionist” than a journalist. Maybe that’s what combining “independent” and “journalist” leads to these days. Only Jonathan can explain that one.

In this response, I’ll tackle some of Cook’s statements—his words, not mine, and no plagiarism or money-making schemes here. I’ll stick to the facts, though I can’t promise my tone won’t wander into sarcasm or humor. After all, I’m neither a journalist nor a professional opinion maker, and I’m not pretending to be. So if my comments come off as a bit cynical or opinionated—well, that’s intentional. And since there’s a lot to unpack, this article will be just the first of several parts.

Jonathan Cook kicks things off with a bang, setting the tone right out of the gate:

For many years I lived just up the road from Megiddo prison in northern Israel, where new film of Israeli guards torturing Palestinians en masse has been published by Israel’s Haaretz newspaper. I drove past Megiddo prison on hundreds of occasions. Over time I came to barely notice the squat grey buildings, surrounded by watch towers and razor wire.

I’m not going to unpack the whole “guards torturing Palestinians en masse” claim just yet (that statement deserves its own moment). Starting with Haaretz makes sense. Sure, it’s considered a respected publication by some, though pretending it’s the beacon of unbiased truth? Not quite. It’s full of opinions—some reasonable, some not. So no, Jonathan, it’s not exactly the gospel.

As for the “squat grey buildings surrounded by watch towers and razor wire” of Megiddo prison—well, yes, most prisons tend to look like that. It’s not exactly Barbie Dreamhouse material.

Shocking, I know!

Regarding the video Cook references—it links to an X-post1 by Mustafa Barghouti. You know, because when you need hard-hitting, unbiased points of view on human rights, Barghouti’s your guy—come on! In the video, we see Palestinian captives on the ground, surrounded by Israeli forces and—brace yourself—dogs, complete with muzzles. Yes, Jonathan—a muzzle. Not exactly a scene out of Cujo. I suppose when you’re aiming for drama, even a standard muzzle can look menacing.

Are there allegations of torture? Sure, and they’re being investigated. If proven true, those responsible will face consequences. To be real, the video Cook is all worked up about? It shows no torture. It shows the handling of suspected terrorists. And let me ask you, Jonathan—how would you propose handling people suspected of horrific terror acts? With kid gloves? Maybe some soft velvet mittens and a cup of herbal tea while we’re at it?

Jonathan moves forward with this striking observation:

There are several large prisons like Megiddo in Israel’s north. It is where Palestinians end up after they have been seized from their homes, often in the middle of the night. Israel, and the western media, say these Palestinians have been ‘arrested,’ as though Israel is enforcing some kind of legitimate legal procedure over oppressed subjects – or rather objects – of its occupation. In truth, these Palestinians have been kidnapped.

Before diving into the facts, take a moment to appreciate the rhetorical flair here. Jonathan drops words like “seized,” “objects,” “occupation,” and “kidnapped” as if he's putting together an anti-Israel keyword strategy. It’s a neat trick, though it feels more like cheap rhetoric than serious journalism. No points for originality, Jonathan.

Now, about this idea that “Israel and the western media” are somehow united in pushing a pro-Israel narrative—really? If anything, the Western media has been far from a cheerleader for Israel. Israel’s actions, including these arrests, have been scrutinized and criticized from all sides for decades. Conveniently, Jonathan leaves out the fact that these very arrests are regularly condemned. So, this whole “nobody’s on the Palestinian side” narrative? That’s not how things stand. Media outlets aren’t exactly queuing up to wave the Israeli flag.

Turning to the actual facts about Israel's prisons and detention facilities: contrary to the dramatic picture Jonathan paints, Israel runs around 30 prisons—and, surprise!—they aren’t all exclusive to Palestinians. Who would’ve guessed? The Israeli prison system houses a mix of people, including Israeli citizens (Jewish, Arab, and others) as well as Palestinians from the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem.

Here's the breakdown:

Prisons for Criminal Offenses: Many of Israel's prisons are just your average, run-of-the-mill facilities for folks convicted of crimes like theft, assault, or drug-related offenses. These prisons primarily hold Israeli citizens, though yes, a few Palestinians convicted of criminal offenses can be found there as well. Not exactly the high-drama scenario Jonathan would have you believe.

Prisons for Security Detainees (Including Palestinians): Then there’s a handful of prisons like Megiddo, Ofer, Ketziot, and Nafha, which house Palestinians detained for security-related offenses. These charges can range from acts of resistance against the occupation (which, as we know, can mean a variety of “activities”), membership in banned organizations, terrorism-related charges, or—and here’s where things get controversial—administrative detention, where detainees are held without formal charges. These aren’t your typical petty criminals; we’re talking security matters here.

Administrative Detention: Speaking of administrative detention, a few prisons and detention centers are specifically set up for this. It’s a system where individuals (mostly Palestinians) can be detained without trial based on classified, secret evidence. Is it controversial? Absolutely. Is it unique to Israel? Hardly.

Yes, Israel uses administrative detention, and sure, it’s controversial. That doesn’t mean this is some uniquely Israeli invention. Plenty of other modern countries detain individuals without formal charges, often in the name of national security. Take Guantanamo Bay in the United States, for instance. People have been held there for years without formal charges, based on classified evidence. Yet, oddly, I don’t see Jonathan penning articles about that particular case of “kidnapping.”

Or how about France? After the 2015 Paris attacks, they invoked state-of-emergency laws that allowed the government to detain people suspected of terrorism without trial. Even today, France’s anti-terrorism laws allow for detention based on classified information. It’s not exactly velvet-gloved treatment there, either.

And then there’s the UK. They’ve used control orders and later Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPIMs) to restrict the movement of individuals suspected of terrorism without formal charges. It's worth remembering that during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the UK detained suspects without trial on a massive scale. Administrative detention was practically a weekend hobby back then.

And we can’t leave out Australia, where Preventive Detention Orders allow the government to hold individuals without charges if they’re suspected of preparing for a terrorist act. It’s not unique to Israel, folks—it’s a standard feature in counter-terrorism playbooks around the world.

So yes, Israel has around 30 prisons, though only a subset are used for Palestinian detainees held on security-related offenses or administrative detention. The rest? They’re housing all sorts of criminals from a variety of backgrounds (so much for the apartheid claim), including Israeli citizens. It’s not the one-sided, single-purpose system some would like to portray. And yes, Israel uses administrative detention—and yes, it’s controversial. Is Israel the only country doing this? Hardly. If Jonathan Cook wants to offer a global critique of this practice, he might want to look beyond Israel’s borders.

Gaza and the West Bank Prisons

What do we know about Gaza and the West Bank and their prison systems? A brief dive into the details should clear things up.

Gaza Strip Prisons and Detention Facilities

The Gaza Strip, run by Hamas since 2007, has its own system of law enforcement, complete with prisons and detention centers. These facilities serve mainly to handle criminal offenses, political prisoners, and, of course, the ever-popular “suspected collaborators with Israel” category.

Prisons for Criminal Offenses: Yes, even Gaza has a regular prison system for the garden-variety criminals—think theft, assault, and drug-related crimes. These prisons are run by Hamas's Ministry of Interior. Nothing too different here, other than being under the control of a “government” that isn’t exactly known for its transparency.

Prisons for Political Detainees: Then there’s the fun side of the prison system—Hamas’s political opponents, especially those tied to Fatah or other factions. Human rights groups? They’re not exactly fans of the arbitrary arrests and political repression happening here. But hey, dissent isn’t exactly welcome in a place like this.

Prisons for Collaborators and Security Offenses: If you’re accused of collaborating with Israel in Gaza, things can get rough. Hamas takes this very seriously, and “harsh conditions” is putting it mildly. In some cases, these alleged collaborators face the death penalty. Who needs due process, right?

Detention Centers and Torture: This is where things get even murkier. Several detention centers are used for interrogations, and reports of torture are not exactly uncommon—especially for political prisoners and those accused of collaborating with Israel.

While the exact number of prisons in Gaza is hard to pin down (likely fewer than 10), it’s clear they exist to keep Hamas’s grip tight. Criminal offenses, political dissent, and accusations of collaboration are all managed internally. And if you’re expecting oversight from international organizations, good luck with that—access is limited, often controlled by Hamas. Not to mention, international organizations may face bias or intimidation, making true transparency even harder to come by.

West Bank Prisons and Detention Facilities

Over in the West Bank, things are a bit more complicated. Prisons and detention centers here are run by both Israel (in areas under Israeli control, especially Area C) and the Palestinian Authority (PA) in Areas A and B.

Israeli Prisons and Detention Centers: Israel runs several military detention centers in the West Bank for Palestinians involved in security-related offenses. The star of the show here is Ofer Prison near Ramallah, where Palestinians accused of “resistance”, banned organization membership, or other security offenses get their accommodations.

Military and Administrative Detention: Administrative detention in the West Bank is based on Israeli military law, allowing Palestinians to be held without formal charges using secret evidence. In Israel proper, the practice is governed by the Emergency Powers (Detention) Law of 1979. Both legal frameworks share a common purpose: preventing security threats while protecting sensitive intelligence that could compromise national security if disclosed.

Palestinian Authority (PA) Prisons: The PA has its own set of detention centers for those who commit theft, drug offenses, and other delightful crimes. You’ll find these mostly in urban areas like Ramallah, Hebron, and Nablus. But the PA isn’t exactly innocent when it comes to locking up political opponents, especially if they happen to support Hamas or other factions challenging their authority.

The West Bank has a dual prison system. Israel runs military detention centers for Palestinians involved in security offenses, while the PA manages a smaller, internal network of prisons for criminal offenses and political opponents. While Israel’s military prisons tend to hold security detainees, many are transferred to larger prisons within Israel. Meanwhile, the PA’s facilities serve as a means of both criminal justice and political control.

Comparison with other countries

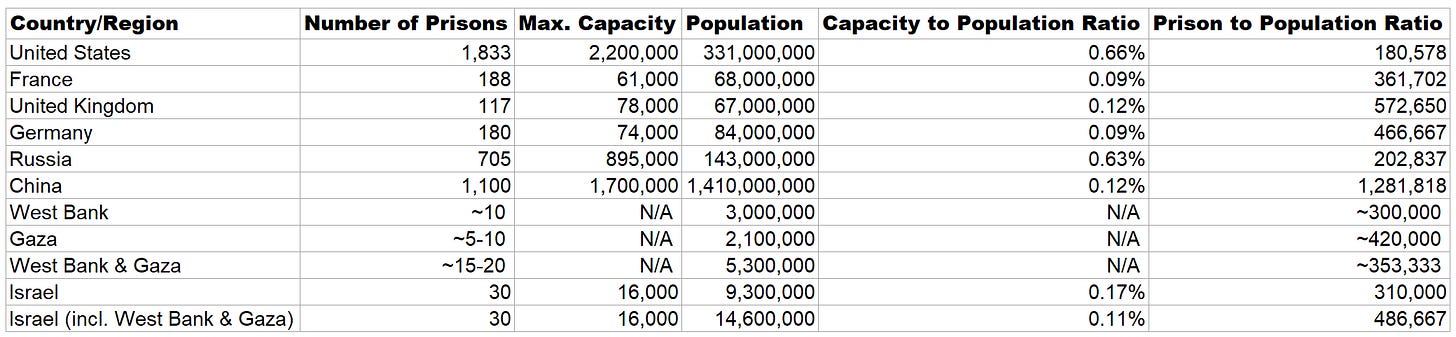

Alright, time to talk numbers. When it comes to prisons and detention facilities, it’s not all about dramatic headlines; it’s about cold, hard data. So, here’s a breakdown of how Israel stacks up against other countries in the world when it comes to prisons, using the numbers from this lovely table2.

Capacity to Population Ratio: Who’s Really Winning?

First up, the Capacity to Population Ratio—this tells us how much prison space a country has per its population. In other words, how many beds are ready for those unlucky enough to land behind bars. The U.S. is the gold medalist here with a whopping 0.66%. Russia’s right behind with 0.63%. Guess when you’re running a former Soviet state or the world’s most prominent superpower, you’ve got to make room for a lot of people who “step out of line.”

Then there’s Israel—at a relatively low 0.17%, not exactly filling every nook and cranny with inmates. France, Germany, and the UK? They’re even lower at 0.09% to 0.12%, which either means they’re good at keeping crime down or, well, not so much into throwing people into prison.

Adding another layer—if we include the populations of the West Bank and Gaza in Israel’s calculations, the numbers drop even further. The Capacity to Population Ratio becomes 0.11%, bringing Israel’s prison capacity ratio almost in line with countries like France and Germany.

And let’s not forget China, holding steady at 0.12%—with a population of 1.4 billion, that’s still a mind-boggling 1.7 million prison beds. But hey, given the scale, it’s no surprise.

As for West Bank & Gaza, those figures are a bit of a mystery—N/A (not available) for capacity. Given the context, though, prison space isn’t the primary focus of attention there.

Prison to Population Ratio: How Many People Share a Prison?

Prison to Population Ratio—this one’s a little more fun. It shows how many people are theoretically served by each prison. So if you ever wondered how many people per prison a country has, here you go.

U.S.: A prison for every 180,578 people! That’s a lot of prisons.

Russia: One prison per 202,837 people. Gotta keep that legacy alive.

China: It takes 1.28 million people to share a single prison, which tells you how big their population really is.

France, Germany, and the UK: These countries are a bit more restrained. In the UK, one prison per 572,650 people. Germany’s slightly better off with one for every 466,667 folks.

Israel: One prison for every 310,000 people, keeping things right around the middle of the pack globally. And if you’re looking at the Prison to Population Ratio of Israel incl. West Bank & Gaza, it hits 486,667, which again makes Israel highly comparable to these European countries. So, while Israel's numbers might initially seem a bit higher, when you consider the full context, it's not that far off from the norm.

West Bank & Gaza: Rough estimates suggest Gaza’s sitting at around 420,000 people per prison, and the West Bank slightly better at 300,000 per prison. Combine them, and you’re looking at 353,333 people per prison. Not exactly spacious—then again, we’re working with different dynamics here.

Is Israel an Outlier?

So, is Israel an outlier in this field? Well, not really. Looking at the Capacity to Population Ratio, Israel’s 0.17% isn’t off the charts compared to heavyweights like the U.S. and Russia. It’s even on the lower side when compared to the world’s biggest economies. Sure, it’s higher than European countries like France, Germany, and the UK—though not by an alarming margin.

As for the Prison to Population Ratio, Israel lands somewhere between the extremes. It’s not building prisons on every corner like the U.S., but it’s also not stretched as thin as China, where millions of people “share” one prison. In fact, when we factor in the West Bank and Gaza with Israel, the combined number of people per prison (486,667) puts it closer to Germany, suggesting it’s far from being an outlier.

It’s all about location!

Next, Jonathan offers his take on the location of the prisons.

The prisons are invariably located close to major roads in Israel, presumably because Israelis find it reassuring to know Palestinians are being locked up in such large numbers. (As an aside, I should mention that transferring prisoners out of occupied territory into the occupier’s territory is a war crime. But let that pass.)

Ah yes, because nothing soothes the soul on a morning commute quite like driving past a prison. While Jonathan’s statement seems to suggest that Israelis get their sense of security from a nice view of prison walls, the reality is a little less cinematic.

To be honest, Israel is a tiny country. It’s not like there’s endless space to tuck prisons away in some far-off wilderness. Nearly all infrastructure—be it prisons, hospitals, schools, or military bases—is close to major roads. Why? Because in a geographically small and densely populated country, everything is near major roads. It’s basic logistics, not some grand psychological reassurance scheme.

In fact, this happens everywhere. Prisons are typically placed near transportation routes in most countries to ensure secure movement of prisoners, make staff commutes manageable, and provide access to services. It’s not like Israel’s breaking some new ground in prison placement strategy here.

Keep in mind that in Israel, where the road network is extensive and population centers are concentrated, it would be difficult to build large facilities far from major roads, even if they wanted to. So Jonathan’s theory about prisons being conveniently placed for “reassurance” feels more like rhetorical spin than anything based in reality.

Now, to give Jonathan a bit of credit, the legal point about the transfer of prisoners from occupied territories into Israel possibly violating international law under the Fourth Geneva Convention? It’s a fair argument, and it’s not one to dismiss lightly. The Fourth Geneva Convention does indeed prohibit the transfer of detainees from occupied territories into the territory of the occupying power. From this legal perspective, there’s a valid case to be made about how this practice could be seen as a violation of international law.

That said, there are other perspectives to consider. Israel, for example, often argues that security concerns and logistical factors necessitate the transfer of prisoners. They maintain that the proximity of these prisons to central Israeli infrastructure allows for better management and security control, particularly in cases involving individuals charged with serious security offenses. The argument here is that it's not so much a breach of international law as it is a necessary measure to ensure national security, especially in the context of ongoing conflict.

Furthermore, while international law provides a framework, enforcement and interpretation of these laws can be highly complex and political. Israel’s stance, supported by some legal scholars, often points to unique security needs that justify these actions, particularly when dealing with acts of terrorism. In this sense, what Jonathan presents as a clear-cut violation is, in practice, a heavily contested legal issue, with both sides offering arguments that make this far from black and white.

So yes, Jonathan raises an important legal question. As with most international law issues, though, it’s not as simple as “this is illegal.” There’s a lot of grey area in how laws are applied in conflict zones, and the reality on the ground often makes hard-and-fast rules difficult to enforce. Israel’s actions may be seen as a violation in some interpretations; however, from their perspective, it’s a response to security needs and logistical realities.

In summary, the reason Israeli prisons are near major roads isn’t about calming the public. It’s about practical, geographic constraints. Jonathan might want to pick another reason for Israel’s road-to-prison proximity, because “reassurance” isn’t it.

And since Jonathan seems concerned about the current placement of prisons in Israel, I’d love to hear his thoughts on where they should be more “accurately” placed. Perhaps a beachfront location with better views? Or maybe nestled in a quiet, remote valley where nobody has to see them? Jonathan, I’m sure you have some great ideas. Here’s a map3 for you—go ahead, point out your ideal locations!

The End?

For now, yes—that’s all. Jonathan’s next point? A real eye-opener:

Even before the mass round-ups of the past 11 months, the Palestinian Authority estimated that 800,000 Palestinians – or 40 percent of the male population – had spent time in an Israeli prison. Many had never been charged with any crime and had never received a trial. Not that that would make any difference – the conviction rate of Palestinians in Israel’s military courts is near 100 percent. There is no such thing as an innocent Palestinian, it seems.

800,000 is undeniably a big number by any metric, and it’s indeed widely cited—including by the Palestinian Authority and human rights groups—as the number of Palestinians imprisoned since 1967 until 2023. But what does this number really mean?

In the next part, we’ll dive into this topic in detail—and yes, we’ll even bring in some math, because the truth shall set you free—eventually, even if it takes some math to get there, man!

Meanwhile, here’s something to ponder—how many people do you think have been incarcerated in the U.S. between 1967 and 2023? Feel free to take a guess and let me know in the comments!

Multiple Sources: https://www.prisonstudies.org, https://www.wikipedia.org/, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/

Adapted from: https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/165587

Jonathan Cook seems to be spending his entire career on coming up with new ways to demonize Israel. His readership can’t get enough of it. Thanks for calling him out.